What the UK Budget Really Means for the Future of the NHS

- Dr Catia Nicodemo

- Dec 22, 2025

- 6 min read

Budget speeches rarely feel like turning points. They are political theatre: a handful of headline policies, a few carefully chosen numbers, and a lot of rhetoric about “building a better tomorrow”. But underneath the slogans, fiscal decisions quietly reshape public services for years to come. This year’s budget, presented by Rachel Reeves, is a good example. It contained no dramatic overhaul of the National Health Service, yet its overall structure may be one of the most consequential shifts in health policy for a decade.

At first glance, Reeves offered little more than warm words about the NHS. She spoke of “record investment”, reiterated the ambition to cut waiting lists, and reaffirmed the government’s commitment to 250 neighbourhood health centres. These remarks were brief—almost cursory. But taken together with the broader tax and spending framework she announced, they hint at something far more ambitious: a rebalancing of how the UK raises and allocates resources for health.

This budget signals movement toward a high-tax, high-investment model, a direction the Treasury has resisted for many years. And it places the NHS right at the centre of that shift.

A Changed Fiscal Landscape

The most important NHS story in the budget is not a specific funding pledge but a change in the UK’s tax structure. Reeves outlined a package that includes:

A prolonged freeze in income tax thresholds

Higher tax rates on property, dividends, and savings

New levies on gambling

A tax on electric vehicles

An extended sugar tax on high-sugar dairy drinks (“the milkshake tax”)

This tax package is not simply about raising revenue; it redistributes the burden upward. More of the health system will be funded by higher incomes and by wealth-related streams, rather than through broad-based tax rises that hit all households equally. For a service as politically sensitive as the NHS, this matters. It is easier to defend increased spending when it appears to be coming from those most able to pay.

Just as importantly, Reeves is broadening the tax base used for day-to-day NHS funding. That may sound technical, but the implications are enormous. A wider and more stable revenue base reduces reliance on government borrowing. Instead of plugging gaps in the NHS workforce or backlog clearance with short-term loans or emergency winter funds, the government is attempting to build a sustainable financial floor under the service.

Figure 1: UK Tax Revenue Over Time

Source: IFS, 2025

This shift doesn’t solve every issue—not even close—but it makes long-term health planning more realistic. Stability is the oxygen of health systems. For more than a decade, the NHS has been breathing in short, anxious gasps, dependent on sporadic cash injections whenever crises break the surface. By anchoring health funding more securely, this budget attempts to provide normal breathing room.

Investment Beyond Hospitals: A Structural Pivot

Budgets are more than spreadsheets; they tell us what kinds of systems governments believe will work. One of Reeves’s most important signals is her desire to shift the centre of gravity away from hospitals and towards primary and community care.

The commitment to create 250 neighbourhood health centres is a telling example. These centres aim to bring together GPs, community nurses, physiotherapists, mental health specialists, and diagnostic services under one roof. Although the details remain thin, the principle is transformative: catch illness earlier, treat people closer to home, relieve pressure on hospitals, and prevent acute crises before they begin.

The UK’s hospital-centric model has grown increasingly unsustainable. A population that is aging, chronically ill, and socioeconomically unequal cannot be efficiently cared for exclusively within acute settings. Every major health system that has improved outcomes while controlling costs—whether in Scandinavia, Spain, or parts of Canada—has done so by building stronger community care.

And this is precisely where the NHS has struggled most. Primary care is overstretched, vacancies are high, and poorly integrated digital systems mean patients bounce between services without continuity. If neighbourhood centres are implemented well—properly staffed, funded, and digitally connected—they could mark a turning point.

But without careful design, they risk becoming new buildings that simply shift pressure around the system rather than relieving it.

The “Milkshake Tax”: Small Policy, Big Implications

The extension of the sugar levy to high-sugar dairy drinks might seem trivial, even gimmicky. But symbolically, it is a significant moment in the fiscal treatment of health. It acknowledges that diet-related disease is not just a clinical problem but a fiscal one.

Obesity and diabetes are two of the biggest drivers of NHS demand. They increase hospital use, GP visits, medication costs, and long-term care needs. Even modest reductions—single-digit percentage improvements in population weight or blood sugar levels—translate into huge savings and improved quality of life.

Public health economists have been arguing for years that prevention requires price signals. If an environment makes the unhealthy choice the cheapest choice, then advice, education, and willpower will always be fighting an uphill battle. The “milkshake tax” is a nudge, not a hammer. But it is an important step in reframing health policy as something that happens across every department, not just within the NHS.

Critics are right to warn about regressivity: lower-income households spend a larger share of their budget on cheaper, high-sugar foods and drinks. Without complementary policies—subsidised healthy food, improved access to fresh produce, targeted support—the levy risks functioning more like a sin tax than a health intervention.

But done properly, the benefits extend far beyond fiscal savings. They include better long-term health for children, reduced risk of chronic disease in adulthood, and a more productive labour force. That connects directly to the next major budget decision.

Ending the Two-Child Benefit Cap: An Unlikely Health Policy

On the surface, lifting the two-child benefit cap is a social policy, not a health one. But its effects on the nation’s well-being are likely to be profound.

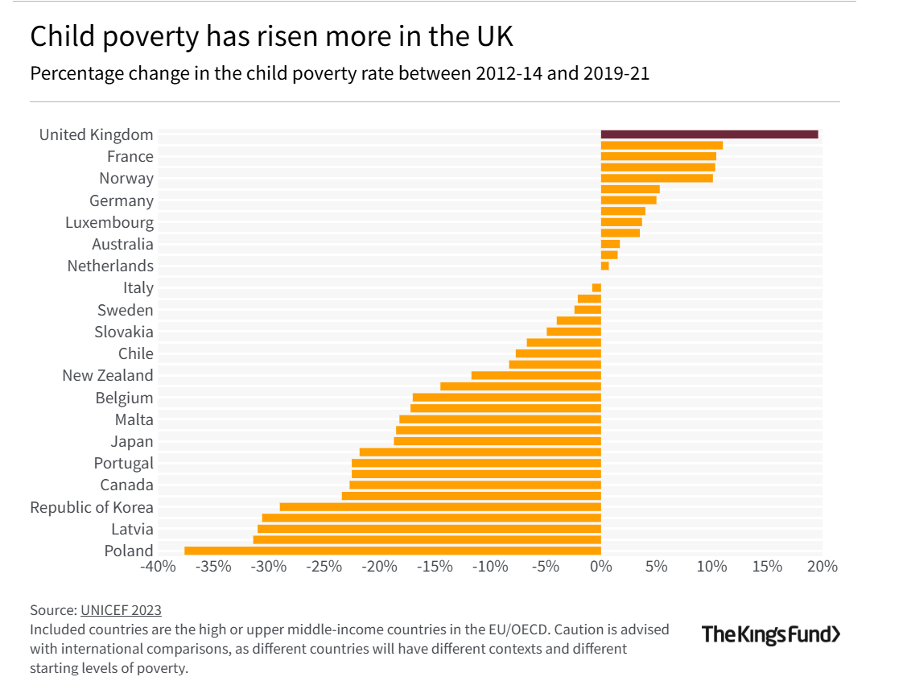

Child poverty shapes adult health in deep and lasting ways. Children who grow up without enough food, heating, or stable housing face higher rates of asthma, developmental delays, obesity, depression, and chronic illness. These harms accumulate, creating lifelong disadvantages and higher NHS use.

By removing a policy that structurally penalised larger families, the government is not just redistributing income—it is reducing future healthcare demand. It is rare for a fiscal measure to function so directly as a preventative health intervention, but this one does.

Figure 2: Childhood Poverty Rates

When combined with the sugar levy, the benefit change forms a coherent strategy: improve childhood environments, support healthier diets, and reduce the burden of preventable disease. These are slow-burn policies. Their effects will not be immediate. But if sustained, they could ease demand on the NHS in ways that hospital funding alone never could.

A High-Tax Model for a Healthier Nation?

Reeves’s budget represents a trade-off: pay more now, receive a healthier, more economically productive population later. It is a gamble, but a rational one.

High-income countries with strong health outcomes—Denmark, Norway, Germany—tend to have higher tax takes and invest more heavily in prevention. The UK has tried for years to maintain Scandinavian expectations with American-level tax resistance, and the result has been predictable: growing waiting lists, thinning workforce morale, crumbling estates, and a health system permanently on the brink.

Yet the transition to a higher-tax model comes with risks:

Economic growth may not rebound quickly enough

Productivity gains may lag behind investment

The political commitment to long-term health may fracture under pressure

A high-tax, high-investment system works only if citizens see their services improving rapidly. If waiting lists remain long, ambulance delays persist, and GP appointments stay scarce, the political legitimacy of the model could unravel.

The Future of the NHS: Stability or Strain?

The budget does not solve the NHS’s immediate problems. Staff burnout, workforce vacancies, hospital overcrowding, and social care shortages will still dominate headlines. But it does nudge the UK toward a different philosophy of health stewardship.

Instead of reacting to crises, the government is trying to shape the conditions that prevent crises. Stronger community care. Healthier diets. Reduced childhood poverty. Broader tax support.

Some of these interventions are subtle, even quiet. But health systems are often transformed not by dramatic reforms but by accumulating small, strategic shifts.

The real question is whether the government can maintain this direction for long enough to see results. Prevention requires patience—something modern politics rarely provides. But if sustained, the policies in this budget could begin to reverse the cycle of short-term firefighting and fragile service resilience that has defined UK health policy for more than a decade.

The NHS has survived under extraordinary pressure. With the right structural support, it could do more than survive; it could begin to thrive again.