Building Sustainable Long-Term Care: Ageing, Integration, and the Future of Health Systems in Europe

- Dr Catia Nicodemo

- Sep 9, 2025

- 5 min read

The world is experiencing an unprecedented demographic shift. The proportion of older people in the global population is increasing faster than ever before, raising urgent questions about how societies can meet the health and social care needs of their aging citizens. According to the World Health Organization, by 2050, one in six people worldwide will be over 65, compared to one in eleven in 2019 (WHO, 2021). This change is not merely statistical; it has significant implications for health systems, economies, and social structures. Long-term care (LTC), which encompasses a range of services designed to support people with reduced functional capacity, is central to this debate. Far from being a minor aspect of health policy, LTC is now emerging as a cornerstone of sustainable health systems in aging societies.

Long-term care is essential because it directly affects health outcomes and quality of life for older adults. A well-designed LTC system ensures that older people can receive continuous, coordinated, and person-centered support. Evidence consistently shows that when LTC is properly integrated with health services, it can prevent avoidable hospitalizations and reduce unnecessary emergency visits. Older adults are at a higher risk for conditions such as falls, complications from chronic disease, and social isolation, all of which frequently lead to urgent hospital visits when left unmanaged. Studies across Europe have shown that integrated LTC services can reduce emergency admissions by up to 30%, primarily through better monitoring, early intervention, and continuity of care (Eurohealth, 2019). This is not simply about relieving pressure on hospitals, but about enabling older adults to live with dignity, independence, and security in their own homes or communities for as long as possible.

The integration of health and social care is often cited as the gold standard for managing the complexity of aging. In practice, this means bridging the gap between hospitals, primary care providers, community services, and social support systems, creating a continuum of care that follows individuals across different stages of need. Integrated models, such as those piloted in the United Kingdom and Scandinavia, demonstrate that when medical and social professionals work together, outcomes improve not only for patients but also for caregivers, who often shoulder a disproportionate burden. Integration enables shared care planning, streamlined communication, and multidisciplinary teams that can anticipate and respond to changes before crises arise. This is essential in the context of aging, where co-morbidities are the rule rather than the exception, and fragmented systems too often leave patients and families struggling to navigate complex bureaucracies.

However, providing effective long-term care requires more than just structural integration. A significant challenge lies in the workforce. Across high-income countries, the LTC sector faces chronic problems with recruitment and retention. Caring for older people is often undervalued, both socially and economically, with low wages, limited career advancement, and physically and emotionally demanding work. The OECD has warned that by 2040, without significant reforms, many countries will face a severe shortage of LTC workers that could reach crisis levels (OECD, 2020). Retention is particularly problematic as high turnover weakens the continuity and trust essential to long-term relationships between caregivers and clients. Professional burnout, coupled with precarious working conditions, makes sustaining a stable workforce extremely difficult. This directly impacts the quality of care and the ability of LTC systems to fulfill their commitments.

The question, then, is how to sustain and improve long-term care in the face of these demographic and workforce challenges. Technology, especially artificial intelligence (AI), is increasingly discussed as part of the solution. While AI cannot and should not replace the human element of care, it can provide powerful tools to support both professionals and patients. For example, AI-powered monitoring systems can detect subtle changes in behavior or health status, enabling earlier interventions that prevent deterioration and reduce hospital admissions. Predictive analytics can identify individuals at high risk of falls or medication-related complications, helping caregivers target resources more effectively. Remote diagnostic tools, combined with AI-assisted decision support, can empower primary care providers to manage complex patients in the community instead of referring them unnecessarily to hospitals.

AI also has the potential to alleviate workforce pressures by streamlining administrative tasks. Documentation and reporting requirements consume a significant portion of caregivers’ time, detracting from direct interaction with patients. Natural language processing and automated record-keeping can lessen this burden, allowing workers to concentrate more on the human aspects of care. Furthermore, AI-driven scheduling and workforce management systems can optimize staff deployment, ensuring that skills are matched to needs and reducing inefficiencies that contribute to stress and turnover. In training, AI-enabled simulation offers workers realistic, adaptable learning environments to improve skills and confidence, leading to higher retention by boosting professional satisfaction.

However, the use of AI in LTC raises important ethical and policy considerations. Privacy, data security, and consent are particularly sensitive when dealing with vulnerable older populations. There is also a risk of exacerbating inequalities if access to AI-enabled care is uneven across regions or socio-economic groups. For AI to deliver on its promise, it must be integrated within a framework of person-centered care with clear guidelines on transparency, accountability, and inclusivity. Policymakers should ensure that technology adoption does not replace investment in people, but rather a complement to boost human capacity.

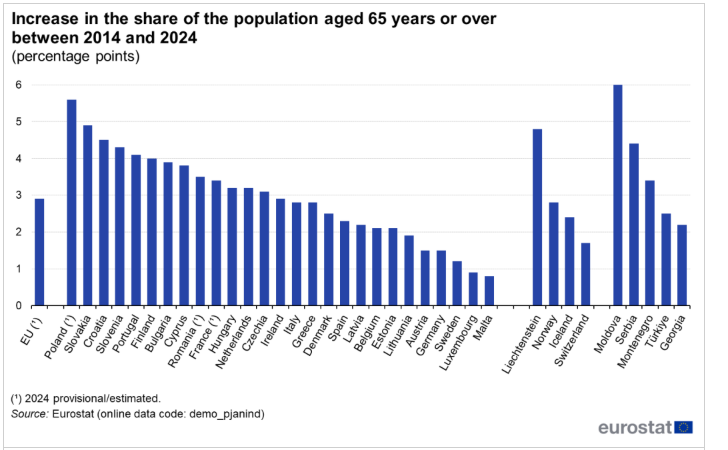

Graphs depicting the scale of aging and the potential impact of integrated LTC highlight the urgency of reform. As shown in global demographic projections, the percentage of the population over 65 is rising steadily, from 6.9% in 2000 to a projected 16.7% by 2050. Simulations of integrated LTC programs also indicate that emergency admissions can be reduced by nearly one-third when continuity and coordination of care are prioritized. These figures underline the dual imperative: to prepare for the demographic changes and to implement care models that successfully improve outcomes while easing the strain on acute health services.

Ultimately, strengthening long-term care is not only a health issue but a societal one. It speaks to how we value older people and those who care for them, both formally and informally. The sustainability of LTC systems will depend on policies that raise the status of care work, provide adequate funding, and foster innovation. Investments must be made not only in technology but also in the people who deliver care, ensuring that they have the skills, support, and recognition needed to thrive in a challenging but vital profession. At the same time, integrated and technologically enhanced LTC must remain firmly anchored in principles of equity and accessibility, so that all older adults, regardless of income or geography, can benefit.

As the demographic transition accelerates, the time for incremental reform is over. Long-term care must be recognized as a core pillar of modern health systems, essential for preventing unnecessary hospital visits and upholding the dignity and independence of older adults. Policymakers, health leaders, and societies at large face a clear choice: either invest now in integrated, sustainable, and technology-driven long-term care systems or contend with increasing emergency admissions, spiraling costs, and widening inequalities in the decades ahead. The evidence is strong, the tools are developing, and the moral obligation is undeniable.

References

World Health Organization (2021). Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report. WHO, Geneva.

OECD (2020). Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly. OECD Publishing, Paris.

Eurohealth (2019). Integrated Care for Older People: Improving Outcomes and Reducing Hospital Admissions. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.