Power and Money on the Platforms: How Streaming Studios Became the New Gatekeepers of Global Culture

- Prof George Batsakis

- Jan 12

- 5 min read

When Netflix announced recently that it would acquire Warner Bros. in an $80-billion mega-deal, the media world was left in shock. Netflix started as a DVD-by-mail service and is now set to own one of Hollywood’s most powerful studios, holding one of the world’s most valuable film and TV libraries. The surprise was not only the amount of the acquisition, but also what it represented: a pure streaming platform taking full control of one of the entertainment industry’s most significant intellectual properties and production infrastructures.

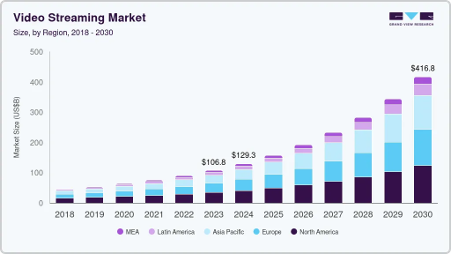

This acquisition can explain how power in the entertainment industry has moved from studios to platforms, from creators to algorithms, and from broadcasters to digital ecosystems. And the reality appears blunter than ever, showing that the streaming wars were never just about shows. They were about control over who gets paid, who is discovered, and who governs the broader global media culture. As shown in Figure 1, global streaming revenues have surged over the past decade and continue to grow at double-digit rates, further proving the rising economic and cultural importance of the industry (see Figure 1).

In this article, I will draw on recent academic research to examine how platform revenue-sharing models, monetization strategies, and platform ecosystem dynamics are restructuring global media. Insights from selected academic work will help us better understand the political economy behind the Netflix–Warner Bros. deal.

Revenue Sharing: The Backbone of Platform Power

Revenue sharing is not a technical detail. It is something more substantial, indicating how power in digital markets is distributed among players. Recent research by Bergantiños and Moreno-Ternero (2025), published in the Management Science journal, shows that revenue-sharing schemes directly determine incentives and bargaining dynamics between creators and platforms. The Spanish authors demonstrate that platforms have the ability to influence not only how much creators earn but also how value is distributed across the ecosystem.

Their article demystifies the real-world tensions that exploded during the 2023–2024 WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes, where writers and actors demanded greater transparency into residuals from streaming platforms. Platforms now act as centralized distributors of value and revenue, deciding which shows are successful, which creators should be rewarded, and which genres are prioritized. The Netflix–Warner Bros. deal is expected to further amplify this power. The reason is that once a platform owns vast IP catalogues and production units, it can channel revenue flows toward internally produced content, thus reinforcing vertical control.

Platform Business Models: How Monetization Shapes Creative Supply

If revenue sharing determines who earns money, business models determine how money is made, and therefore, which content gets produced. Carroni and Paolini (2020) show, in a formal model of streaming competition, that platforms’ strategic choices among subscription, advertising, and hybrid models have significant implications for content acquisition and investment. Their work highlights how different monetization schemes generate distinct incentives for exclusivity, catalogue size, cost control, and platform differentiation. As shown in Figure 2, Netflix’s subscriber base has exceeded 300 million globally, giving the platform tremendous visibility into user preferences.

Overall, there are three known business models in streaming platforms. First, the so-called ‘Subscription-first platforms’, such as Netflix, Max, and Apple TV+. Their business model prioritises user retention with a heavy investment in original titles/content. They also prefer exclusive content to differentiate from rivals, while using algorithmic recommendations to minimise customer churn. This model creates a structural bias toward bingeable series, global IP, and continuous production cycles. Second, we have the ‘Advertising-first platforms’, with YouTube and TikTok being the most successful players. These platforms prioritize scale over exclusivity, incentivize and reward user-generated content, and emphasize algorithmic integration. Under this model, there are numerous creators, individual bargaining power is low, and visibility depends on non-transparent recommendation systems. Third, there are the so-called ‘Hybrid ecosystems’ with known platforms being Disney+ and Amazon Prime Video. These platforms compete beyond streaming. For Amazon, Prime Video cements retail loyalty for its customers, while for Disney, streaming extends monetizable IP across merchandise and theme parks.

We can assume that the Netflix–Warner Bros. deal signals Netflix’s attempt to fill its own structural gap by gaining control over IP, merchandising potential, and cross-platform synergies, moving closer to Amazon’s and Disney’s ecosystem logic.

Ecosystem Relations: Platforms as Cultural Policymakers

Extant research shows that platform power stems not only from distributing content but from governing the entire creator–user–partner ecosystem. More specifically, the recent study by Wlömert et al. (2024) explores how platforms balance the interests of creators, users, and advertisers, demonstrating that platforms are in a position to ‘regulate’ both visibility and monetization, ultimately deciding which content gains traction and popularity and which is sidelined. Similarly, the research by Ma, Mai & Hu (2024) examines the “relationship triangle” of UGC platforms and shows that platforms constantly mediate between creators’ incentives, audience engagement, and advertiser demands. Their findings strengthen the idea that platforms are not just intermediaries but rather shape markets through algorithmic and economic governance.

These insights apply equally to Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon Prime, even though they rely less on user-generated content. The mechanism is similar. Algorithms decide what is visible, platforms set the economic rules, and creators and studios must adapt or risk becoming irrelevant in the new landscape.

The Netflix–Warner Bros. acquisition strengthens this governance role. Vertical integration means Netflix can commission, produce, distribute, and monetize content end-to-end. It can also leverage data to shape creative decisions, while negotiating from a dominant position with external studios and talent. In short, Netflix becomes not just a distributor but a private cultural policymaker.

Conclusion: The New Hierarchy of Cultural Power

The traditional media hierarchy in which studios create, distributors deliver, and audiences decide, has been replaced by a platform-centric model. In fact, platforms are now in a position to control discovery via algorithms, monetisation via revenue-sharing rules, and production via acquisitions and originals. While creators negotiate upward, studios negotiate sideways, while users negotiate unknowingly by feeding the data systems that shape their own recommendations.

With its Warner Bros. acquisition, Netflix now better controls both the means of cultural production and distribution. No Hollywood studio in the last century has had this level of end-to-end insight into audience behaviour, nor this level of control over how culture circulates.

Streaming is no longer a technological innovation; it is a reconfiguration of cultural governance. What is certain after this phenomenal deal is that creators will push for greater transparency and fairer monetization, studios will double down on franchise IP to retain bargaining power, platforms will seek ever deeper integration, including AI-driven production, regulators will increasingly scrutinise platform visibility algorithms, and users (subscribers) will remain shaped by platform curation.

The Netflix–Warner Bros. deal marks the beginning of a new phase in the industry and political economy of entertainment. Platforms do not just distribute culture, but set the rules, capture the value, and increasingly own the cultural assets themselves.

References

Bergantiños, G., & Moreno-Ternero, J. D. (2025). Revenue sharing at music streaming platforms. Management Science.

Carroni, E., & Paolini, D. (2020). Business models for streaming platforms: Content acquisition, advertising and users. Information Economics and Policy, 53, 100883.

Ma, R., Mai, Y., & Hu, B. (2025). User-Generated Content Platforms: Managing the Relationship Triangle. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management.

Wlömert, N., Gourville, J. T., Hosanagar, K., Dolata, M., & Otto, P. E. (2024). The interplay of user-generated content, content providers, and platforms. Marketing Science (Frontiers in Marketing Science).