State capital on the pitch: Why Gulf funds are buying clubs and whole leagues

- Prof George Batsakis

- Jul 29, 2025

- 5 min read

State-owned investors from the Gulf and China are no longer satisfied with trophy hunting. They are building multi-use assets that deliver money, diplomatic clout, and brand lift all at once. By placing sovereign wealth at the heart of European football, LIV Golf, and soon perhaps basketball, they are rewriting the playbook of global sport. Below, we break down the logic, show what the numbers look like, and map the governance questions that follow, drawing on the latest research, including fresh evidence on how sovereign-wealth-fund (SWF) transparency varies across countries (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2023).

How the business model works

Traditional owners chase either medals or profits. State-capitalist investors layer on a third return: soft power. Some call this “diplomatic venture capital,” as each shirt sponsor, stadium name, and away-kit launch turns into a rolling advertisement for the home state. State-backed owners seek three types of returns. First is the money. Bigger TV deals, more sponsors, and better results on the field drive club prices way up. For example, the evaluation of Manchester City FC rose from under £200 million in 2008 to about £4 billion today. Second is diplomacy. VIP boxes become meeting rooms, pre-season tours lead to visits in foreign capitals, and club events provide a friendly setting for signing broader business agreements. UK–UAE trade teams, for instance, often plan trips around City matches so they can mix football with deal-making. Third is nation branding. Premier League games draw roughly three billion viewers each season, so every match promotes the owner’s home country. The impact is real: after Manchester City won three domestic trophies in 2019, tourist arrivals from the UK to Abu Dhabi increased by eight percent, demonstrating how success on the pitch can translate into increased visitor numbers on the ground.

What the data show

Table 1 highlights four headline deals in which sovereign investors from the Gulf bought or created major sport assets between 2008 and 2022. The transactions start with Abu Dhabi’s £200 million purchase of Manchester City FC in 2008 and move through Qatar’s entry into Paris Saint-Germain FC (valued then at roughly €100 million), Saudi Arabia’s £300 million takeover of Newcastle United FC in 2021, and finally Saudi Arabia’s multi-billion-dollar launch of the LIV Golf League in 2022. Although football dominates, the list already stretches into new territory (an entire golf competition), showing how the model is scaling. Deal sizes jump from hundreds of millions to well over two billion dollars, and the stated motives shift from basic club turnaround to broader nation branding, Vision 2030 diversification, and tourism promotion, underscoring how financial, diplomatic, and image goals increasingly blend in state-capitalist sports investments.

Table 1. Flagship state‑capitalist sport deals

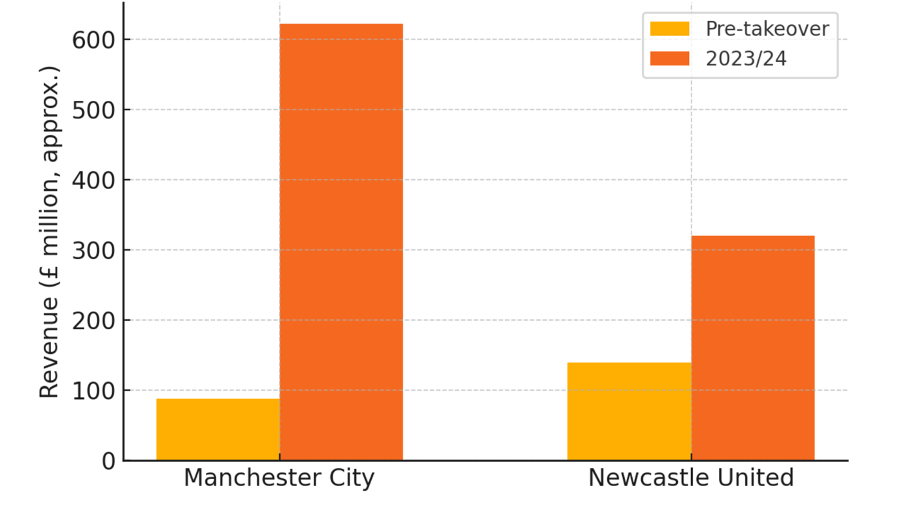

Figure 1 compares club revenue before and after state-owned investors took charge. Manchester City’s yearly income jumped from roughly £90 million before the 2008 Abu Dhabi takeover to about £620 million in the 2023/24 season. This represents a more than sevenfold increase. Newcastle United shows a smaller but still striking rise: from about £140 million before the Saudi Public Investment Fund arrived in 2021 to roughly £320 million three seasons later. The figure clearly indicates that state-backed ownership is linked to sharp growth in club revenue, driven mainly by bigger commercial and media deals rather than match-day ticket sales.

Transparency and governance: the missing piece

A recent study published in the Journal of International Business Policy reveals that the transparency of Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) varies significantly with the home-country governance and the origin of the wealth (oil versus financial reserves). Funds from more autocratic systems score lower on disclosure metrics, creating a multi-level agency problem between citizens, politicians, and fund managers (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2023). Why does that matter on the pitch? First, when SWFs lack transparency, they face stricter “fit-and-proper” ownership tests. Both the Premier League’s existing checks and tougher EU rules are now being drafted. Second, opaque structures also erode fan confidence. Surveys show that supporters are more likely to protest when they cannot see who ultimately controls their club, as recent demonstrations at Newcastle and PSG illustrate. Third, low disclosure even slows the deal process. The Premier League’s owners and directors test took about 18 months for Newcastle’s Saudi-backed takeover, compared with just four months for Todd Boehly’s well-documented purchase of Chelsea.

Recent headlines that show the model scaling

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund keeps raising the stakes in golf. Its latest round brings the LIV Golf budget to about $3.9 billion, giving a firm grip on the sport’s new league. In France, Qatar-owned PSG FC is pressing ahead with plans for a large new stadium, tying the project to a club valuation of roughly €4 billion and a broader real estate play in Paris. Across the Atlantic, the NBA quietly adjusted its rules in 2024 to let sovereign wealth funds own up to 20 percent of a team through private-equity vehicles, opening the door for state money to enter US basketball for the first time.

These moves raise three main worries for leagues and regulators. First is competitive balance. Unlimited state funds can skew salary races, so hard caps and clear financial-fair-play rules are key. Second is political influence. Limiting the voting rights of state-controlled owners can help keep league decisions neutral. Third is the risk of reputation damage if human-rights issues surface, which argues for independent due diligence panels. One blanket rule will not fit every case, though. Research shows that a fund’s behaviour usually reflects the politics back home, so disclosure demands, and control limits need to be tailored to each investor’s track record and governance style (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2023).

Concluding thoughts

We still have some big questions to answer. First, do the new stadiums, transport links, and jobs that arrive with a state-backed owner last beyond the early excitement, or do they fade once the spotlight moves on? Second, can the “buy a team, boost a brand” playbook that started in football work the same way in sports like basketball or Formula 1, or will those leagues react differently? Third, as these funds receive more global attention, will they feel pressure to disclose how they operate back home, or will their low-transparency habits remain the same? With plenty of money still waiting to be invested and US leagues only now allowing state capital through the door, the next ten years will be interesting to watch as these issues unfold. It is also a key period for regulators, who must establish rules that allow new capital to flow in without compromising fair play or public trust.

References

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., Grosman, A., & Wood, G. (2023). “Cross-country Variations in Sovereign Wealth Funds’ Transparency.” Journal of International Business Policy, 6, 306-329.

Kearns, C., Sinclair, G., Black, J., Doidge, M., Fletcher, T., Kilvington, D., ... & Santos, G. L. (2024). ‘Best run club in the world': Manchester City fans and the legitimation of sportswashing?. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 59(4), 479-501.

Media sources: ESPN, Financial Times, Reuters